Dogs Through Time: A Timeline of the Human–Dog Bond

Tracing 30,000 years of companionship, adaptation, and shared history

Welcome! You are about to step into one of the greatest stories ever told, the journey of dogs and humans together. Imagine it with me: thousands of years ago, wolves and people stood on opposite sides of the firelight, curious, cautious, and slowly learning that life could be better when shared. From those first tentative steps grew a partnership unlike any other, reshaping not only how we lived but who we became.

As you move through this timeline, I invite you to experience the ages of discovery, survival, and companionship. You will see how dogs became hunters’ allies, steadfast guardians, loyal herders, healers in spirit, and beloved family members. Every era reveals a new chapter of courage, cooperation, and trust. By the end, I hope you will feel what I do, that dogs are not simply our pets. They are our partners in survival, our reflections in history, and our companions in every step forward. Come along with me, and let’s celebrate this extraordinary bond together.

— Mason Lusk, CCRP

Early Wolves & Humans (c. 30,000–12,000 BCE)

In the late Ice Age, human hunter-gatherers and wolves shared the same tough landscapes. Over thousands of years, some wolves lingered near camps, scavenging scraps and benefiting from human fires and vigilance. People discovered these watchful animals could act as early alarms and tracking partners. Through gradual mutual tolerance, the first steps toward domestication began.

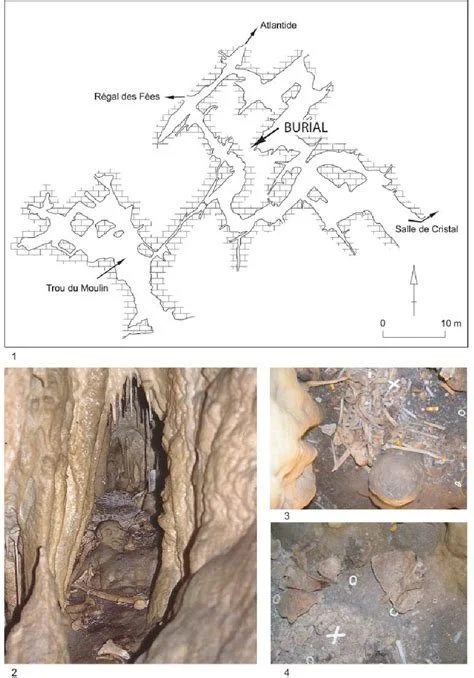

Finds such as canid remains at Goyet Cave (Belgium, >30,000 years ago) and later late-Pleistocene burials suggest a slow shift from wild wolf to camp-friendly proto-dog. By roughly 20,000–15,000 years ago, human groups in parts of Eurasia were living alongside distinct dog-like canids, indicating parallel pathways toward early domestication rather than a single event.

As the Ice Age waned (after ~12,000 BCE), this cautious coexistence deepened into cooperation: tracking, guarding, and shared warmth around the fire. These late-Pleistocene partnerships laid the groundwork for the enduring human–dog bond that would flourish in the Holocene.

Prehistory: First Companions (20,000–10,000 BCE)

Archaeological discoveries show that wolves began moving closer to human camps as Ice Age hunters spread across Eurasia. Over generations, some wolves adapted to scavenge, track, and warn. These proto-dogs were gradually welcomed into human groups, forging the first interspecies partnership in history. Evidence suggests domestication may have occurred independently in multiple regions, from Siberia to the Fertile Crescent.

Burials from this period highlight the growing emotional bond. At Bonn-Oberkassel in Germany, a human and a dog were laid to rest together more than 14,000 years ago. In Israel, Natufian graves contain puppies nestled in their owners’ arms. These are not signs of utility alone — they are proof that affection, trust, and kinship were already central to the relationship.

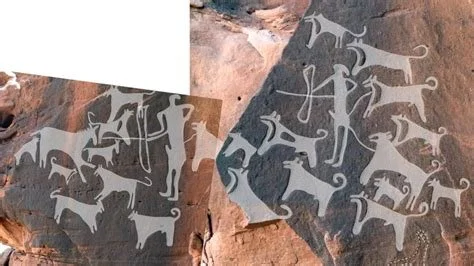

Rock carvings from Arabia, dating back nearly 9,000 years, depict dogs hunting alongside humans, with lines that may represent leashes. These are the earliest known images of guided dogs, showing that people had already begun shaping canine behavior to fit the needs of cooperative life.

Early Farming Societies (10,000–3,500 BCE)

With the Neolithic Revolution, humans began living in permanent settlements. Dogs quickly became essential to this new way of life. They guarded stored grain, barked at intruders, and worked as partners in hunting. Their presence allowed villages to feel more secure and gave families a loyal ally in a rapidly changing world.

Archaeological evidence from Anatolia and the Levant shows that dogs were often buried within or near homes, a practice that suggests their role was both protective and spiritual. At Çatalhöyük in modern-day Turkey, dog bones have been found among human burials, further proof of their integration into society.

Figurines from the Indus Valley depict short-tailed village dogs, already distinct from wolves in body shape. These models show that people were not only using dogs for work, but also representing them as part of their cultural identity. By the dawn of the Bronze Age, the dog had already become a fixture of family and community life.

Bronze Age Civilizations (3,500–1,200 BCE)

In the first great civilizations, dogs were no longer just companions — they were sacred. In Mesopotamia, dogs were associated with the healing goddess Gula, and small clay figurines of crouching or striding dogs have been found buried in temple foundations. These figures may have served as spiritual guardians, protecting both households and the sick.

In Ancient Egypt, depictions of greyhound-like hunting dogs appear in tomb paintings. Pharaohs kept sleek hounds for sport and protection, and inscriptions record dogs with names like “Brave One” and “Reliable.” Some were buried with their masters, wrapped in linen and honored in ways that mirrored the care given to humans.

Across the Indus Valley, terracotta figurines of short-tailed dogs suggest their role as protectors of households. On Crete and in Anatolia, frescoes show dogs accompanying hunters, emphasizing their importance in food gathering and elite leisure. By the end of the Bronze Age, dogs were fully woven into the fabric of civilization: protectors, healers, hunters, and companions, immortalized in art and ritual.

Dogs in the Classical Period

From 500 BCE to 500 CE, dogs were integral to daily life across Greece, Rome, and other classical cultures. In Greece, writers like Xenophon described hunting dogs in detail, praising their courage and training. Breeds such as the Laconian hound were renowned for their speed and discipline in the hunt, while smaller lapdogs were celebrated in poetry and domestic art.

In Rome, dogs served as guardians, hunters, and beloved companions. Powerful Molossian mastiffs were kept for protection and warfare, while more delicate breeds rested in the villas of wealthy Romans. The “Cave Canem” mosaic from Pompeii, reading “Beware of the Dog,” is a striking reminder that canine guardianship was as much about pride as it was about security.

Archaeological evidence reveals the depth of Roman affection. Multiple dog cemeteries and gravestones, or monotaphs, have been uncovered, bearing inscriptions that grieve for lost companions. One epitaph for a dog named Margarita reads, “My eyes were wet with tears, our little dog, when I bore you to the grave… in return for so great a love.” These stones show that people of the Classical world cherished dogs as family.

In Persia, Zoroastrianism placed dogs at the center of spiritual life. They were seen as protectors against evil, and sacred rituals involved dogs watching over the dead to guard the soul’s journey. Texts such as the Vendidad describe dogs as uniquely pure creatures, deserving of care and respect. Breeds like the Saluki, swift and elegant, became symbols of nobility while also carrying sacred significance in Zoroastrian practice.

Beyond the Mediterranean and Persia, dogs played important roles across Asia. In China during the Han Dynasty, palace dogs like early Pekingese were kept as status symbols, while in Japan, early Shiba Inu and Akita types were bred for hunting and guarding. The Classical Period was truly global in its celebration of dogs — as hunters, protectors, companions, and even spiritual guardians of the human soul.

Dogs in the Middle Ages

From 500 to 1500 CE, dogs remained essential to human life across cultures. In Europe, they were central to noble hunting traditions, with greyhounds and spaniels appearing in illuminated manuscripts as symbols of nobility and skill. Large mastiffs guarded castles and farmsteads, while herding breeds kept flocks safe. Dogs were not only workers but also companions, lying at the feet of knights in tomb carvings as emblems of loyalty and devotion.

In the Islamic world, attitudes toward dogs varied, yet hunting hounds such as the Saluki were prized and appear in Persian art and poetry. These slender, swift animals were celebrated as noble companions of hunters and rulers. In China, palace traditions of keeping small guardian breeds like the Pekingese and Shih Tzu flourished, their presence seen as both ornamental and spiritual. In Japan, early Akita and Shiba Inu types served as loyal protectors, woven into regional identity.

Across the Americas, Indigenous cultures developed and maintained unique breeds. The Techichi, ancestor of the modern Chihuahua, held ritual significance in Mesoamerica, often associated with guiding souls in the afterlife. In the Arctic, sled dogs continued to be bred and trained for survival, pulling loads and helping people thrive in harsh climates. These roles show how dogs adapted alongside human societies in every environment.

Folklore carried the spirit of these bonds. The Welsh tale of Gelert immortalized the sacrifice of a faithful hound, while Japanese legends told of dogs who rescued lost travelers or protected children. From manuscripts to monuments, dogs were honored across continents as guardians, helpers, and beloved companions. By the end of the Middle Ages, many breed lineages were firmly established, laying the foundation for the remarkable diversity of dogs that would follow in later centuries.

Dogs in the Renaissance & Early Modern Era

Between 1500 and 1800 CE, dogs entered a new cultural spotlight. In Europe, the Renaissance brought with it a fascination with symbolism and portraiture, and dogs were painted alongside nobles and royalty as emblems of fidelity, loyalty, and wealth. Small breeds like the Pug and Italian Greyhound appear in portraits of aristocrats, including the famous paintings of European courts by artists such as Titian and Van Dyck. Hunting remained central to noble identity, with setters and spaniels refined for birds, while mastiff-type dogs protected estates.

In the Islamic world and Persia, the Saluki remained a treasured companion of rulers and hunters, appearing in richly illustrated Persian manuscripts. Its image represented grace, nobility, and spiritual purity. In Mughal India, royal miniatures often depicted dogs at the sides of emperors, reflecting their symbolic place in courtly life. Meanwhile, in Japan, Akita and Shiba Inu breeds served as loyal guardians, celebrated in local stories for their bravery and devotion.

Exploration and colonial expansion spread European breeds to new lands, and dogs adapted to entirely new environments. Sailors brought terriers and mastiffs aboard ships, while missionaries and settlers introduced small companion breeds to the Americas and beyond. Indigenous traditions continued alongside this exchange: in the Arctic, sled dogs such as early Huskies were vital to survival, and in Mesoamerica, descendants of the Techichi remained woven into spiritual practices and daily life.

By the close of the early modern period, dogs had become powerful cultural symbols worldwide. They appeared in paintings, literature, and royal courts, not only as workers or protectors but as living emblems of devotion and status. This era laid the foundation for the 19th century’s fascination with formalized breeding and kennel clubs, turning cultural prestige into defined breed standards.

Dogs in the 19th Century

The 19th century marked a turning point in how humans related to dogs. Industrialization and urbanization meant that more people were living in cities, and dogs increasingly became companions in homes rather than solely workers in fields. This period also witnessed the birth of formal dog breeding and kennel clubs, with the establishment of The Kennel Club in Britain in 1873 and the American Kennel Club in 1884. These organizations codified breed standards, transforming working types into formally recognized breeds.

Breeds beloved today gained prominence in this era. Collies were celebrated for their intelligence and pastoral grace, immortalized in art and later literature. Bulldogs, once used in blood sports, were reshaped into companions admired for their toughness and loyalty. Terriers proliferated in Britain as both working dogs and fashionable urban companions. In Europe’s courts, Pugs and Spaniels were popular lapdogs, reflecting the tastes of the growing middle class.

Around the world, dogs remained tied to survival and tradition. In Japan, the Akita Inu became a symbol of loyalty and cultural pride, while in the Arctic, Huskies and Malamutes were essential for sled travel and trade across frozen landscapes. In India, pariah dogs thrived in villages as resilient, semi-feral companions, embodying the closeness of dogs and humans outside the realm of kennel clubs.

Culture and literature of the 19th century often cast dogs as moral exemplars. Paintings of Victorian families frequently included dogs as symbols of fidelity. Writers such as Sir Walter Scott praised the loyalty of their canine companions, and early dog shows attracted crowds fascinated by the variety of breeds. By 1900, the stage was set for the modern era of dogs: diverse, standardized, and more deeply tied to family life than ever before.

Dogs in the Early 20th Century

At the dawn of the 20th century, dogs were increasingly seen not only as workers but as beloved companions. Urban families embraced smaller breeds like Boston Terriers, Pugs, and Toy Spaniels, while rural communities continued to rely on Collies, Sheepdogs, and Terriers for herding and pest control. The diversity of breeds celebrated in dog shows reflected the changing relationship between humans and their canine partners.

Literature and art brought dogs into public imagination. Jack London’s *The Call of the Wild* (1903) and *White Fang* (1906) captured the spirit of sled dogs, elevating their courage and resilience into symbols of survival and loyalty. Dogs also appeared in early film reels, delighting audiences with their intelligence and personality.

The First World War (1914–1918) showcased dogs in unprecedented numbers. German Shepherds, Dobermans, and Airedale Terriers served as messengers, guards, and Red Cross rescue dogs. Millions of soldiers returned home with stories of canine bravery, deepening the bond between dogs and people. It was during this period that Rin Tin Tin, a German Shepherd rescued from a battlefield, began the journey to becoming a global film star.

The Rise of Dog Racing (1908–1930 CE)

In the early 20th century, dogs leapt from household companions and working partners into the arena of organized sport. Two traditions in particular — sled racing in the Arctic and greyhound racing in American cities — became national spectacles between 1908 and 1930, shaping the public’s imagination of speed, endurance, and canine athleticism.

The first nationally recognized sled dog race was the All Alaska Sweepstakes, held in 1908. Covering 408 miles between Nome and Candle, the race tested both human and canine endurance across brutal Arctic conditions. Breeds like the Siberian Husky and Alaskan Malamute proved their worth as unmatched endurance athletes. The race drew international press and introduced the world to the idea of dogs competing in long-distance feats of stamina.

Meanwhile, in 1919, the first mechanical-lure greyhound race was held in Emeryville, California. Inventor Owen Patrick Smith sought to replace traditional live-hare coursing with a humane, mechanical alternative. By 1920, the first official greyhound track opened, and within a decade, tracks had spread across the United States and the UK. Greyhounds, sleek and swift, became symbols of speed and modern leisure culture, drawing crowds eager for the spectacle.

Greyhound racing also created one of the earliest large-scale connections between athletic dogs and rehabilitation. Retired greyhounds, whose careers often ended while they were still young, became the focus of adoption programs beginning in the mid-20th century. Their muscular build, history of injury, and sensitive temperaments highlighted the need for structured recovery, careful conditioning, and supportive home environments. In many ways, the journey of the retired greyhound — from racer to family companion — helped introduce the concept of canine rehabilitation and long-term care into the public conversation.

These developments marked the first time dogs were celebrated in large-scale, national sporting arenas. Whether pulling sleds across frozen wilderness or sprinting around city tracks, dogs became athletes in their own right — admired, wagered upon, and cheered as champions of endurance and speed. The rise of dog racing reflected the modern era’s fascination with performance, competition, and the evolving bond between humans and their animals.

Yet the growing popularity of dog racing also exposed troubling realities. Greyhounds were often bred in large numbers to produce only the fastest competitors, leaving thousands of unwanted dogs at risk of neglect or euthanasia. The intense pace of training and racing could lead to injuries, while living conditions for some kennels were criticized as inadequate or inhumane. These concerns cast a shadow over the sport’s glamorous image.

Public debates about gambling, animal welfare, and commercialization eventually led many countries and U.S. states to restrict or outlaw greyhound racing. While sled dog sports evolved into cultural traditions and endurance challenges, commercial greyhound racing increasingly came under scrutiny. Today, the legacy of dog racing is remembered both for its celebration of canine athleticism and for the ethical questions it raised about how society treats animals in the name of entertainment.

Balto & Togo: Heroes of the Serum Run (1925 CE)

In the winter of 1925, the small town of Nome, Alaska faced a deadly diphtheria outbreak. The only hope for survival lay in transporting life-saving antitoxin across nearly 700 miles of ice and snow. A relay of sled dog teams carried the serum in brutal conditions, enduring storms and subzero temperatures. Among these teams, two dogs rose to lasting fame: Balto and Togo.

Balto, a black Siberian Husky, led the final leg of the journey into Nome. His arrival with the serum captured the imagination of the world. Newspapers hailed him as a hero, and in 1925, a statue was erected in New York’s Central Park with the inscription: “Endurance · Fidelity · Intelligence.” Balto became a symbol of canine courage and devotion, celebrated in schools, parades, and children’s stories for decades.

Yet many mushers insisted the true hero was Togo, a Siberian Husky of unmatched endurance. Togo led his team across the longest and most dangerous stretch of the relay — over 260 miles of frozen terrain, including the perilous crossing of Norton Sound. At twelve years old, Togo’s courage and leadership saved precious hours, making it possible for the serum to arrive before the epidemic spread beyond control. Today, historians often call Togo the greatest sled dog who ever lived.

Together, Balto and Togo’s legacies remind us that heroism takes many forms. One became the celebrated public face, the other the quiet savior of the longest and hardest miles. Their story is a testament to teamwork, endurance, and the extraordinary bond between sled dogs and their human partners. Modern sled dog races like the Iditarod trace their inspiration directly back to the Serum Run of 1925.

In history, Balto and Togo stand not just as canine athletes, but as healers — whose courage under impossible odds saved an entire community. Their pawprints still mark the shared journey of humans and dogs, reminding us of the strength found in loyalty, perseverance, and trust.

The mushers themselves became legends too. Leonhard Seppala, Togo’s handler, was revered for his skill, toughness, and unshakable faith in his dog team. His partnership with Togo became an example of how human instinct and canine endurance could align to achieve the impossible.

Balto, however, found himself thrust into fame in ways few working dogs ever did. He and his teammates toured the United States, appeared in public exhibitions, and even inspired early films. While many criticized the sensationalism, Balto’s story introduced millions of people to the grit and sacrifice of sled dogs.

The fame brought controversy as well. Some argued that Balto’s recognition overshadowed Togo’s longer and more difficult run. For decades, Togo’s achievements were overlooked in popular culture, though historians and mushers continued to honor his unmatched contribution. This tension highlights how narratives of heroism are often shaped by public perception rather than the full story.

Over time, both dogs found their rightful place in history. Togo was celebrated by mushers and Arctic communities, and in recent years, films and books have restored his reputation as the Serum Run’s true endurance hero. Balto remains beloved as the brave face of the final sprint into Nome — together, they represent different but equally vital forms of heroism.

Their legacy lives on in the Iditarod Trail Sled Dog Race, which began in the 1970s as a commemoration of the Serum Run. Each year, mushers and dog teams honor Balto, Togo, and the unsung dogs of 1925 by retracing parts of the historic trail. The race celebrates not just speed, but endurance, partnership, and respect for Alaska’s sled dog traditions.

Balto and Togo also shaped how dogs were viewed in the broader culture. They became symbols in children’s literature, statues, and films, embedding the idea that dogs are not only companions but also lifesaving heroes. Their stories inspired generations to see sled dogs as partners in human survival and exploration.

Today, Balto and Togo remain cultural icons. Balto’s statue in Central Park continues to attract visitors from around the world, while Togo’s story has gained new life in modern media, ensuring that both dogs — one the celebrated finisher, the other the tireless trailblazer — stand side by side in history as testaments to courage, loyalty, and the unbreakable bond between humans and dogs.

.jpg)

Dogs in Wartime (1914–1945 CE)

From the trenches of World War I to the battlefields of World War II, dogs became trusted comrades. They delivered messages, located the wounded, guarded supply lines, and boosted morale. Their stories of bravery became symbols of loyalty in times of global crisis.

One of the most celebrated was Sgt. Stubby, a stray Boston Terrier mix who served with the U.S. 102nd Infantry Regiment in World War I. Stubby survived 17 battles, warned soldiers of incoming gas attacks, and even captured a German spy. He became the first U.S. Army dog officially given rank and later met three presidents, embodying courage and devotion on the battlefield and at home.

Another canine legacy was Rin Tin Tin, a German Shepherd puppy rescued from a bombed kennel in France during World War I. Adopted by an American soldier, Rin Tin Tin went on to star in dozens of Hollywood films during the 1920s and 1930s. His fame made the German Shepherd one of the world’s most popular breeds and turned a wartime survivor into a cultural icon of loyalty and intelligence.

Thousands of dogs served as Red Cross rescue dogs in Europe during both wars. Trained to find wounded soldiers, they carried medical supplies in saddlebags and led medics back to the injured. Their work saved countless lives in the forests, fields, and ruins of battle-ravaged Europe, often at great risk to themselves.

In World War II, the Doberman Pinschers of the U.S. Marine Corps became famous in the Pacific theater, where they patrolled beaches, warned of ambushes, and delivered messages under fire. Known as the “Devil Dogs of the Pacific,” many gave their lives in service. A bronze memorial on Guam today honors their sacrifice.

Other wartime dogs also left their mark. Chips, a German Shepherd–Collie–Husky mix, served with U.S. forces in World War II and received honors for heroism after attacking an enemy machine-gun nest. Smoky, a four-pound Yorkshire Terrier, was found in a foxhole in New Guinea and became a mascot, entertainer, and therapy dog for wounded soldiers, demonstrating that even the smallest companions could bring immense comfort in war.

Wartime dogs were more than tools of conflict — they were comrades, entertainers, mascots, and healers. Whether rescuing soldiers, starring in films, or simply offering comfort during dark days, their loyalty bridged the gap between battlefield and home front. Their legacy endures in memorials, films, and the continuing tradition of military working dogs today.

After World War II, many nations formally recognized the value of canine service. Military dog training programs became standardized, ensuring that future generations of soldiers could rely on canine partners for detection, scouting, and protection.

In conflicts such as Korea and Vietnam, dogs continued to play vital roles. Scout dogs patrolled jungles, detected ambushes, and located hidden enemy camps. Handlers often described their dogs as lifesavers, preventing countless casualties.

By the late 20th century, dogs were recognized not just as companions of war, but as highly skilled specialists. Breeds such as German Shepherds, Belgian Malinois, and Labrador Retrievers became the backbone of modern military and police K-9 units worldwide.

Today, military working dogs are trained to detect explosives, locate weapons caches, and track enemy movement. Their unmatched sense of smell allows them to uncover threats long before humans can, making them essential in counterterrorism and peacekeeping missions.

In law enforcement, dogs serve as K-9 officers alongside human partners. They assist in searches, crowd control, narcotics detection, and suspect apprehension, bringing both speed and precision to police work. Many departments consider them sworn officers in their own right, honoring them with badges and memorials.

Beyond combat and policing, dogs now serve in specialized security roles. Airport K-9 units screen luggage for explosives, border patrol dogs track smugglers, and search-and-rescue dogs respond to disasters, proving that their service extends far beyond the battlefield.

The journey from trench mascots to elite specialists reflects the evolving bond between humans and dogs. Whether in war, law enforcement, or disaster relief, modern service dogs carry forward the same courage, loyalty, and devotion that made their wartime ancestors legendary.

Dogs in the Cold War Era

Between 1951 and 1975, the world’s shifting politics and rapid technological change made dogs visible in entirely new arenas. They were not only companions and workers but ambassadors of science, healing, and culture. From the launch pads of the Soviet Union to the guide dog schools of Europe and America, canines stood beside humanity in its most daring ventures.

In 1957, the Soviet Union shocked the world by sending Laika, a mixed-breed stray from Moscow, into orbit aboard Sputnik 2. Laika became the first living creature to circle the Earth. Although her mission was fatal, her story captured global headlines and turned her into a symbol of sacrifice, courage, and the ethical dilemmas of science. Other space dogs such as Belka and Strelka followed, returning safely to Earth and proving that space travel for living beings was possible.

At the same time, guide dog programs expanded across Europe and North America. Originating in Germany after World War I to assist blinded veterans, these programs gained global recognition by the mid-20th century. German Shepherds became the face of service work, trained to help the visually impaired navigate busy city streets. Their presence marked a profound shift: dogs were not just companions but partners in independence and dignity.

Therapy and service roles broadened further. Hospitals and rehabilitation centers began to welcome dogs as part of recovery programs, recognizing their calming presence and ability to encourage physical movement. This was the foundation of today’s animal-assisted therapy, where breeds from Labradors to Golden Retrievers became trusted allies in healing both body and spirit.

Cold War militaries also invested in canine service. Both NATO and Soviet forces trained dogs for patrol, detection, and security, especially along tense border zones like the Berlin Wall. German Shepherds dominated this work, chosen for intelligence and discipline. Stories circulated of patrol dogs who formed deep bonds with handlers, underscoring the human element in even the most rigid military settings.

Popular culture reflected this growing intimacy. Children’s books and films portrayed dogs as loyal heroes, from Disney’s *Lady and the Tramp* (1955) to *Old Yeller* (1956), which moved audiences with its themes of love and loss. The era also saw the continued rise of Lassie as a television icon, cementing the Collie as one of the most recognizable dogs in the world.

By 1975, dogs were woven into every part of public life — from cutting-edge science and Cold War politics to living rooms, hospitals, and schools. They had proven themselves as heroes in war, pioneers in space, healers in clinics, and stars on screen. The Cold War era revealed the extraordinary adaptability of dogs, showing that wherever humans ventured, dogs would follow — faithfully and bravely.

Dogs in the Late 20th Century

From 1976 to 2000, dogs entered a new era of global visibility as both rescue heroes and beloved family members. Advances in veterinary medicine, shifting social values, and the growth of mass media meant dogs were no longer seen only in their working roles. Instead, they were recognized as healers, helpers, and cultural icons in a rapidly modernizing world.

Search-and-rescue dogs gained international recognition during disasters. German Shepherds, Labradors, and Border Collies were trained to locate survivors in collapsed buildings, mines, and earthquake zones. In 1980, rescue dogs in Italy located victims of the Irpinia earthquake, while American dogs became vital responders during hurricanes and floods. Their courage elevated them as quiet heroes whose work often meant the difference between life and death.

Therapy dogs also rose to prominence in hospitals, schools, and nursing homes. Scientific studies confirmed what many already knew: that canine companionship reduces stress, lowers blood pressure, and encourages physical activity. Golden Retrievers and Labrador Retrievers became the primary faces of therapy and service programs, valued for their patience, intelligence, and steady temperaments. Their role expanded from guiding the visually impaired to assisting with mobility, seizures, and emotional care.

In popular culture, dogs captured hearts across books and film. Disney’s *The Fox and the Hound* (1981) explored friendship and loyalty across divides. Real-life tales like *Marley & Me*, though published in the early 2000s, reflected the late-century trend of celebrating dogs as central members of households. By the 1990s, entire genres of family films revolved around dogs, from *Beethoven* to *101 Dalmatians*, ensuring that new generations grew up with dogs as cinematic stars.

Breed popularity also shifted in this period. The Labrador Retriever rose to become the most popular breed in the United States by the 1990s, admired for its versatility as both a family dog and working partner. Meanwhile, Yorkshire Terriers, Shih Tzus, and Pomeranians thrived in urban households, reflecting the growing trend of small companion dogs suited for apartment living.

Dogs also featured in international news. The story of Hachiko, the faithful Akita of 1920s Japan, gained renewed global fame in the late 20th century, especially after the unveiling of his statue at Shibuya Station became a landmark for travelers worldwide. His tale of loyalty resonated strongly in a century marked by social upheaval and rapid change.

By the end of the 20th century, dogs were firmly established as healers, companions, and media icons. They searched for survivors in disasters, provided therapy and independence to people with disabilities, and filled movie screens and family photo albums alike. In these decades, dogs completed their transition from guardians and workers to fully recognized members of human families worldwide.

Hachikō: The Loyal Akita of Shibuya (1923–1935)

The photograph on the left shows Hachikō, the faithful Akita who waited at Tokyo’s Shibuya Station every day for his owner, Professor Hidesaburō Ueno, even after Ueno’s sudden death in 1925. For nearly ten years, Hachikō returned to the station at the same hour his master’s train had once arrived. His quiet vigil touched the hearts of commuters and became a national symbol of loyalty.

On the right is the bronze statue of Hachikō, unveiled in 1934 near the very spot where he had kept his daily watch. Remarkably, Hachikō himself was present at the ceremony. The statue was later rebuilt after World War II and remains one of Tokyo’s most iconic landmarks — a popular meeting place and a lasting tribute to devotion beyond death.

Hachikō’s story has since been told in books, films, and memorials worldwide, ensuring that his vigil lives on as one of the most powerful stories of the human–dog bond. The photograph and statue together remind us how a single dog’s loyalty became a legend that continues to inspire people across cultures and generations.

Dogs in the 21st Century

The 21st century has elevated dogs to a new place in human society: not only companions and workers, but family members and cultural ambassadors. From the aftermath of the September 11th attacks to the rise of global social media, dogs have become visible symbols of loyalty, comfort, and resilience in a rapidly changing world.

In 2001, the heroism of search-and-rescue dogs during the 9/11 tragedy captured worldwide attention. Breeds such as German Shepherds, Labradors, and Golden Retrievers worked tirelessly alongside first responders, locating survivors and offering comfort amid devastation. Images of dogs wearing protective booties in the rubble of New York became enduring symbols of courage and hope.

Service and therapy dogs expanded into nearly every corner of life. From assisting veterans with PTSD to providing emotional support in schools, airports, and hospitals, dogs became essential partners in health and wellness. Labradors and Golden Retrievers remain the most common service breeds, though smaller dogs such as Poodles and Spaniels are increasingly valued for specialized tasks.

Social media transformed how people share their love for dogs. Internet-famous dogs like Boo the Pomeranian, Tuna the Chiweenie, and Shiba Inu “Doge” became global icons, their images spreading across memes, merchandise, and fundraising campaigns. For the first time in history, individual dogs could reach millions of people directly, shaping trends, humor, and even philanthropy.

Science deepened our understanding of the canine bond. Genetic research mapped the ancestry of modern breeds, revealing their shared heritage from ancient wolves. Studies on oxytocin and human-dog interaction confirmed what owners long suspected: that dogs actively influence human physiology, lowering stress and strengthening emotional bonds. Veterinary advances extended lifespans, allowing senior dogs to thrive longer as cherished family members.

Cultural works kept dogs at the center of storytelling. Films like *Marley & Me* (2008) and *Hachiko: A Dog’s Tale* (2009) dramatized the bittersweet devotion dogs bring into human lives. Documentaries and literature on working dogs, rescues, and therapy partners highlighted the breadth of canine roles in modern society. Dogs today are as much media figures as they are family companions.

By the present day, dogs embody the diversity of human life itself. They serve in police and rescue units, star in viral videos, support children learning to read, and provide comfort in hospitals and disaster zones. The story that began in prehistoric camps and ancient temples now lives in our homes and online networks, where every wag, bark, and pawprint continues to shape the shared journey of humans and dogs.

Bretagne: 9/11 Search and Rescue Dog

This photograph shows Bretagne, a Golden Retriever who served as a FEMA Urban Search and Rescue dog during the aftermath of the September 11, 2001 attacks. Alongside her handler, Denise Corliss, Bretagne worked tirelessly at Ground Zero, navigating unstable rubble to search for survivors and provide comfort to rescue crews.

Bretagne became one of the most recognized canine responders of 9/11, symbolizing the courage and compassion of hundreds of search-and-rescue dogs deployed in the days after the tragedy. Her service extended beyond that event — she later responded to hurricanes Katrina and Rita — before retiring to a life of community service as a reading dog for children.

When Bretagne passed away in 2016 at the age of 16, she was honored with a hero’s farewell in Texas. Her story continues to remind us that dogs are not only rescuers in times of crisis but also healers who bring comfort and hope in the darkest of times.

Present Day: In Gratitude to Our Companions

As we arrive at the present, we pause to look back with gratitude. For over 30,000 years, dogs have walked beside us, from the first fireside partnerships to battlefields, farms, laboratories, and family homes. They have guarded our doors, carried our burdens, rescued us in times of crisis, inspired our stories, and brightened our darkest days. In every era, their courage, loyalty, and love have shaped human history.

This timeline has shown us hunters’ allies, wartime heroes, space pioneers, therapy companions, entertainers, guardians, and faithful friends. Dogs have proven themselves in roles as varied as the challenges of humanity itself. Yet no matter the task, they have remained constant in their devotion, never asking for more than kindness, care, and the chance to stand at our side.

In gratitude for all they have given us, I hold a simple hope for the future: that we may give back to dogs even a fraction of the loyalty and joy they have given us. That we may honor their history by ensuring their health, protecting their dignity, and cherishing their companionship. To care for dogs is to repay an ancient debt, one written through through millineas of cooperation and companionship.

Mason Lusk, CCRP